The Rise, Fall and Revival of James Street

- Robert Cekan

- 05 Jan 2018

Take a walk down James Street and you’ll see a neighbourhood bursting with life. Residents are chatty, business owners are smiling and the energy is palpable. For most, this is the James Street we know and love — but it wasn’t always this way. Go back a few decades and James Street is telling of a much different tale; one where big business crippled local business owners, degenerating the street into a hive of criminal activity and empty store fronts. It took several factors to push James Street back to its original glory, and those efforts continue to make waves to this day. This is a story of the rise, fall and revival of James Street.

The Rise

Since its inception, James Street (originally named Lake Road) has been the center of attention for visitors and immigrants in Hamilton. First settlers from England, Scotland, Ireland, Italy, Germany, Portugal and Greece would be introduced to Hamilton via James Street — many of whom would live and conduct business directly on it. The fusion of all these backgrounds created an exciting and diverse culture for James Street that was cherished among Hamiltonians.

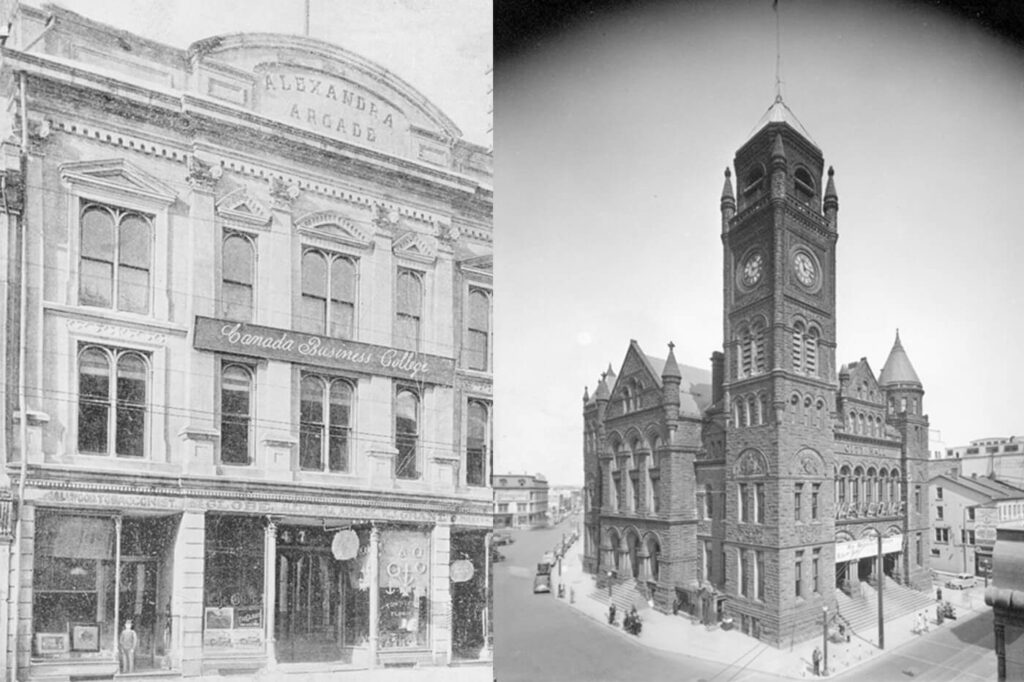

As James Street grew in popularity, it became the main strip to showcase businesses’ and institutions’ status, ability and prowess. Thus, many of Hamilton’s finest architectural marvels were built on James Street including Hamilton’s first skyscraper The Pigott Building, Christ’s Church Cathedral, St. Paul’s Presbyterian Church, Alexandra Arcade, the original Hamilton City Hall, John W. Foote VC Armoury, and CN Railway James Street Station (now LIUNA Station) to name a few plus countless buildings and shops run and owned by the locals.

The flurry of activity, excitement and development made James Street truly one of the greatest places to be in Southern Ontario for well over a century, continually blooming and growing in popularity. Cue World War II.

The Urban Renewal Plan

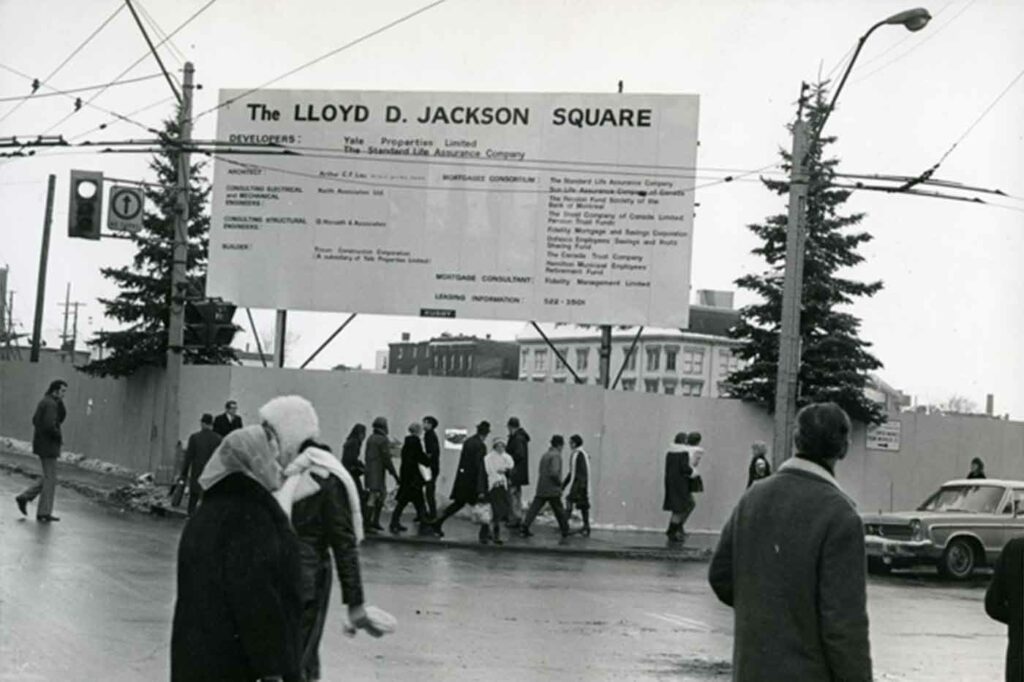

By the end of the Second World War, devastated global economies had taken their toll on urban communities across the Western World and Hamilton was no exception. A proposed urban renewal plan was set forward which included converting/widening smaller streets into through streets and constructing large shopping complexes in place of small shops. Feeling additional pressure to compete with fast-growing Toronto, the people of Hamilton wanted something new to freshen up the downtown core and inject new business to the city. Their answer was a civic centre named Jackson Square.

Hamiltonians were torn about the proposed civic centre. On one hand, the completion of Jackson Square would be the makeover needed to bring Downtown Hamilton back to relevance. Doing so, however, meant residents would have to part with several long-standing businesses and buildings in order to make Jackson Square a reality. The cost of progress is hardly ever cheap.

Once Hamiltonians got word of what the original plans called for — plenty of open space, pools, an ice rink, sculptures and gardens — residents were eager to greenlight Jackson Square as these were all desirable for the core. With the majority of residents in approval, the City went ahead and expropriated many long standing businesses in order to make room for Jackson Square. Expropriation was particularly easy as there was no thought to preservation or heritage at that time (this mentality didn’t truly arrive until the last quarter of the 20th century).

But when funding from CMHC was halted, the tab had to be picked up by the municipality, meaning many of the higher-end features Hamiltonians were promised were no longer deemed to be financially viable. The plan was scrapped in favour of a centre that could better produce revenue; one that viewed many of the features residents wanted as peripheral.

When Jackson Square opened in 1970, Hamiltonians could finally explore this widely altered final product. Despite deviating from the original plan so drastically, people loved shopping there and Jackson Square became an economic success for several years. After all, this shopping mall was new and people were excited to visit it.

Just a few doors down, Eaton’s, a popular department store that bought the Alexandra Arcade building in 1927, continued to modify and expand their site until they came within eight feet of City Hall. All that stood between Eaton’s and Jackson Square was the City Hall building which, to Eaton’s, viewed the City Hall building as an impediment to traffic flow from the new mall. As maintenance costs for the City Hall building grew, council approved construction of a new (now current) City Hall located at Main and Bay Street. By the time Eaton’s was eyeing the property, the City Hall building located between the two structures had already vacated staff to the new office. Thus, Eaton’s “bought the City Hall site when it was vacated and demolished the building, replacing it with a two storey addition to connect their store to Jackson Square” (Hamilton Public Library). The two separate structures now formed to make one massive shopping complex.

Both Jackson Square and the attached Eaton’s department store were thriving… but at what cost?

The Decline

During the construction of these massive complexes, many of the business owners that were displaced due to the expropriation of their shops failed to sustain business in their new locations. The convenience and novelty of Jackson Square completely took business away from the streets by centralizing patrons under one roof. Local business owners operating on the street couldn’t compete against the shopping mall and were forced to close at a rapid pace.

Some of the most architecturally stunning buildings that attracted people to the streets (like the old Hamilton City Hall, Griffin Opera House & Alexandra Arcade) as well as the rows of small restaurants and shops were now gone. Additionally, the continued widening of streets for cars disincentivized people from walking by foot, making it even harder for storefronts to attract customers.

By the early 1980s, approximately 80 storefronts in the James Street North area were empty. The street appeared abandoned and attracted crime such as prostitution and drugs.

At the same time, Hamiltonians were also quickly growing tired of Jackson Square. Sure, it was nice at first since it was new but the lack of those originally-promised facilities (gardens, pools, etc.) didn’t make for a great returning experience in the long-run. Even basic amenities such as wheelchair access and cheap parking were absent and continued to deter shoppers over time.

With Lime Ridge Mall opening on the Mountain in 1981, dissonance grew as Downtown Hamiltonians realized just how cheated they were. The contrast between the two shopping malls was evident with Jackson Square being criticized as feeling outdated and cavernous in comparison. It wasn’t long until shoppers soon ditched Jackson Square in favour of grander shopping experiences offered by better malls, big-box retailers and higher-end brands. With mall traffic dipping, the delinquency from the street was now spreading to the lowly-visited shopping centre.

Now both the street and the main shopping centre had earned a bad reputation as a place to avoid. James Street was on life support.

The Revival

Jackson Square had to continually innovate and add if it were to retain patrons. The completion of the Sheraton Hotel and Copps Coliseum (now FirstOntario Centre) were some of the measures taken in battling concerns and raising optimism for the Downtown centre, but that alone wouldn’t be enough to fix James Street.

Then in the mid-80s, a group of merchants decided they needed to work together in order to revive the street into the positive and thriving area it once was. The team responsible established the Jamesville BIA (Business Improvement Area) and while this BIA faced its share of criticism, they certainly made strides in helping improve the street. Some of their accomplishments included securing a grant to fund the hiring of a student to work on market research and advertising, working with the City of Hamilton to eliminate the rush hour route parking in order to make parking available all day long and obtain low interest loans for storefront renovations which most merchants took advantage of. The Jamesville BIA also submitted an application to the City to renovate the streetscape, which helped bring new lighting, planters, sidewalks and parkettes. Interesting side note: the parkette located at James & Wilson Street has a plaque commemorating the Jamesville BIA’s inception and contains a buried time capsule that is to be opened in 2038.

Other important changes that aided James Street’s revival in the 80s included converting the street from a one-way to a two-way and opening a Police department retail location at the corner of James and Barton Street, which was open 24/7 with paired officers continuously patrolling the streets (this system was the first of its kind in Ontario).

As this was occurring, Jackson Square’s poor property management mixed with a market saturation of franchise retailers prompted tenants to vacate their stores from the mall with Hamiltonians once again being forced to come back to the street for alternatives. By this point however, James Street had made leaps and bounds in progress and did well in retaining those who gave James Street and the businesses located on it a second chance. The influx of new shoppers swayed more small businesses to open up which in turn drew even more shoppers.

By the early 90s, the street was alive and well again with most storefronts being occupied. There was a wide variety of merchants, with a stronger presence of the arts than ever before; people were willing to take risks on James Street again. Many pioneers of the renewed arts scene from the 2000s (such as Mixed Media, Centre[3], You Me Gallery, and Hamilton Artists Inc.) gave other artists the confidence to turn their passions into their own shop or studio. Especially when compared to Toronto, commercial real estate in Hamilton was a bargain and offered artists and business owners a tremendous amount of space for the price. Soon enough festivals such as Artcrawl and Supercrawl, which celebrate local artists, would grow organically and draw in even more talent to the area with each iteration.

Jackson Square’s recovery, however, took a much longer time than James Street itself. It wasn’t until very recent changes like the opening of the 55,000-square foot Nation’s Fresh Foods grocery store in 2013 and unveiling of the newly expanded LCBO in 2015 has Jackson Square felt new energy within the bones of its structure.

And the Eaton’s? Even after connecting itself to Jackson Square, that huge department store only lasted a few decades until Eaton’s decided to tear their entire store down in the late 1980s to make way for the new Eaton Centre which opened in 1990, only to be closed in 1999 and sold in 2000 to become what is now known as the Hamilton City Centre. While this centre still faces massive vacancy, even it is making a comeback.

The New Wave of Revival

As Toronto’s escalating house prices continue to setback home ownership for young people, Millennials from the GTA have ventured further out in hopes of finding a comparable city lifestyle at a lower cost. It turns out that Hamilton is the answer many were looking for.

And while cheap housing may have been one of the biggest drivers for renewed interest in our city, it’s what people have discovered that’s kept them here. A re-emergence of the arts, world-class festivals, boutique shops and specialty restaurants have challenged new-comers’ preconceptions of Hamilton; James Street being a shining example.

The Internet has also been a real paradigm shift in how we find awesome, local shops and activities. Online virality of newly discovered hot spots has amplified the interest for visiting Hamilton and multiplied the audiences for niche shops. The demand is here and people can easily share their experiences with their friend circles. Ongoing operation of these unique shops are sustained by the increased consumer base and give reason for aspiring business owners to make the leap, no matter how specialized their store or gallery may be.

Since the Jackson Square debacle, it’s amazing how supportive downtown Hamiltonians are of small business over corporate franchises. It would appear that we’ve learned the importance of choosing small business over large. That’s because when we choose local, we stand behind not only small business owners, but Hamiltonians. We keep the heartbeat of the city alive; the city we call home.

Comments 0

There are no comments

Add comment