The Private, Public, and the Possible

- John McCurdy

- 01 Aug 2016

PPPs and the Preservation of Heritage Properties

Returning to Hamilton in the spring of 2013 after living out west for five years, I would soon find myself discussing with then City of Hamilton Ward 1 Councillor Brian McHattie a shared passion for local history preservation. During our meeting, he would invite me to assist him in completing Hamilton’s new Downtown Built Heritage Inventory (DBHI), a comprehensive list of local properties of demonstrable “heritage interest.” The hope, he explained, was that they might then be added to the official list of properties protected under the province’s Ontario Heritage Act from demolition and indiscriminate redevelopment.

The long-term integrity of Hamilton’s built heritage remained fundamentally in question during the summer of my return. The previous year, for instance, Julie Baldassi had anxiously asked in Spacing Toronto whether anyone was prepared to save downtown Hamilton’s older buildings, “demolition by neglect” remaining a looming threat in many instances. How, she asked, “to attract investors” in search of a bargain, while “preserving the cultural integrity of heritage buildings”? This tension, she accurately predicted, was certain to persist.

Indeed, by late 2012, just such a flashpoint case would rear its head. Wanting the City to establish a new Gore heritage district, Sean Burak would later report in Hamilton Magazine, Hamilton’s Heritage Committee had asked council to designate 18-28 King Street East a series of properties of significant “historical interest” at imminent risk of being demolished. Council, Burak had explained, would vote against doing so, only to see the property’s owner apply for demolition permits over that year’s Christmas break for all buildings in question.

Within a year (though still at the proverbial eleventh hour), City Council would designate the contentious properties, effectively thwarting their demolition and compelling their owner to negotiate the preservation of aspects of its most significant heritage features. This past June, a Hamilton Spectator article would report, a final compromise deal, preserving half of the various property’s historic facades and ensuring development consistent with Hamilton’s downtown character, would be successfully achieved.

Conflict over the integrity of Gore’s built heritage would undoubtedly shape City Council’s decision the following March to vote roughly one thousand downtown properties onto the provincial heritage list, a measure then incoming City of Hamilton General Manager of Planning and Economic Development Jason Thorne would later describe as “groundbreaking,” given that 350 heritage buildings had by then been demolished in Hamilton since the 1970s.

However, the Gore heritage conflict – and no doubt others that received less or no media coverage – seemed, in some quarters, to raise the issue as to whether private, profit-oriented enterprise should invest in the restoration and redevelopment of commercial and industrial heritage properties.

Arguably, the Government of Ontario had anticipated such objections in 2005 when it moved to strengthen the Ontario Heritage Act’s anti-demolition provisions. “We must show property owners and the business community that preserving our heritage makes good economic sense,” its Minister of Culture would insist in a public statement that year. In the narrow sense, the City of Hamilton had also anticipated the above, establishing its Commercial Heritage Improvement and Restoration Program in 2004, which offered financial assistance to owners of commercial and industrial properties classified as heritage buildings. That same year, meanwhile, University of Waterloo researcher Rebecca Goddard-Bowman would cite evidence that “tech companies [had] discovered the marketing benefits associated with a historic building as an address” and that “heritage preservation” had been shown to serve “as a catalyst for advancing economic development and growth.” Indeed, as author Gordon Fulton writes in the Canadian Encyclopedia, private for-profit involvement in heritage conservation in Canada dates to the 1970s and has since “slowly converged on the field to capitalize on the growing niche market for reused heritage buildings that had developed with the country’s emerging sense of nationalism and history.”

The Hamilton Club would host an invitation only “Economics of Heritage Conservation” session in November 2013, sponsored in part by urbanicity Magazine, and attended by leading developers, building owners, real estate investors and architects. Though the session would report measurable growth in the market for “rehabilitated heritage buildings” and profile specific examples of profitable built heritage adaptive reuse projects in province, the opening lines of a subsequent Hamilton Spectator report on the meeting would declare: “There is money to be made in bringing old, vacant, or decrepit buildings back to life, but it doesn’t come easy.”

Perhaps as an antidote, it would go on to report in August 2015 on what seemed to qualify as a commercial-built heritage redevelopment success story: Historia Building Restoration had profitably – if laboriously – purchased, re-furnished, and resold a property on John Street North near King Street East.

Meanwhile, the Real Estate News would suggest in a subsequent October 2015 article that the issue often came down to realtors avoiding heritage properties – there were 7,000 commercial or commercial/residential ones in the province at the time – because they felt they lacked the necessary expertise to effectively deal with them. Very often, it would add, commercial heritage property success stories had depended on “clever” reuse and redevelopment, a point echoed in a more recent Real Estate Management Industry News article, which explicitly calls for “creative thinking” in cases of private heritage building restoration or reuse projects.

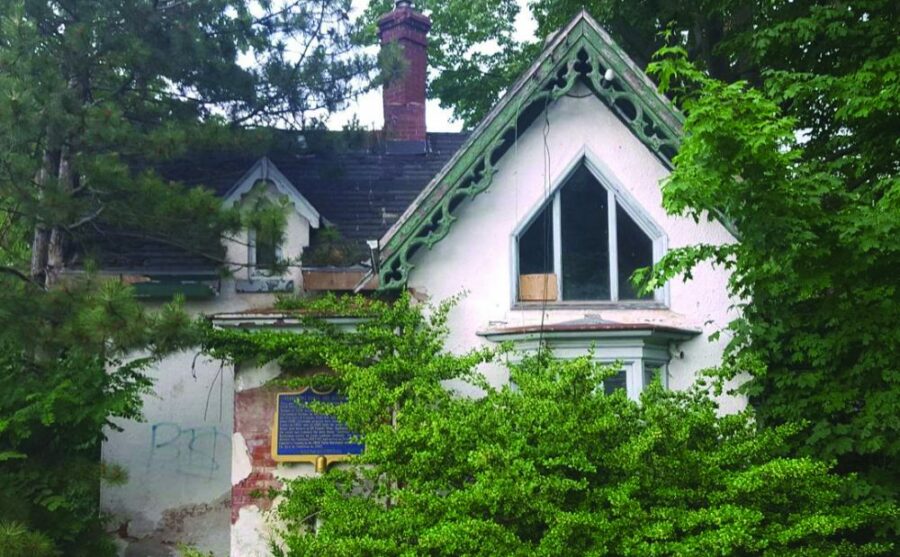

In cases where heritage properties are publicly owned or controlled, however, private developer interventions have an obviously different significance. As of this past June, for instance, Hamilton’s historic Auchmar estate, designated a heritage property in 1999, will remain a City of Hamilton asset, while being leased long-term to an appropriate third party, capable of forwarding a sound business plan and of directly investing in Auchmar capital upgrades. This, and scenarios like it, raises questions over the appropriateness of the future of public-private built heritage conservation and redevelopment partnerships (PPPs) in Hamilton and other Ontario communities.

In 2015, for instance, the Canadian Conservation Institute would suggest that heritage conservation PPPs were still relatively new and untested. The option, with much qualification, has acquired significant traction in the United States. There, in 2013, a joint UNESCO/University of Pennsylvania study would argue that “PPPs work well in some built-heritage circumstances, and less well in others,” its author describing them as “deeply situational.”

Its authors advocate a two-step, project-by-project test. Firstly, does it balance “flows of economic and cultural value” and, secondly, are provisions of private and public goods in balance? If the first variable is out of balance, they explain, “the integrity of conservation or market viability will be at risk.” If the second, “there will be neither legitimacy nor demand for the goods provided.” Good decisions, they add, ultimately must be made by politicians in partnership with experts and the public.

Likewise, a 2014 U.S.-based Getty Conservation Institute study has noted that “a better understanding of … when and how [PPPs] may be used to assist in achieving conservation aims is needed.” In particular, governments need “to invest in developing … governance structure[s]” that ensure private interests “participate in a way that meets community expectations for appropriate conservation that sustains the heritage places they cherish.”

It is perhaps instructive to be mindful of Vanessa Hicks’s admonition, forwarded in her 2013 University of Waterloo Master’s Thesis on community regeneration and built heritage resource in Hamilton, that “old or historic buildings which have been altered unsympathetically can create a bad precedent for further development which puts these resources at risk of losing their integrity or being demolished.”

Auchmar Estate Operations Plan – PED12193(a)

On June 22, 2016, Hamilton City Council voted to keep the entire Auchmar Estate – buildings and grounds – in the public ownership of the City of Hamilton. The motion passed by City Council reads as follows:

(a) That the Auchmar Estate Operations Plan, attached as Appendix “A” to Report PED12193(a), be received;

(b) That Tourism and Culture Division staff be directed to continue with stabilization work obligated under the terms of the Heritage Conservation Easement administered by the Ontario Heritage Trust and to maintain the heritage resource in a stable condition with annual Capital Block funding;

(c) That the Auchmar Estate and grounds remain in Public Ownership of the City of Hamilton;

(d) That City staff in the Real Estate Section and the Planning & Economic Development Department be authorized and directed to explore a long-term lease or operating and management agreement, which is to include that capital repairs and maintenance be the financial responsibility of the lessee or the manager/operator, with any interested non-for-profit private parties; such as the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry XIIIth Regiment Auchmar Trust or other not-for-profit organizations, and report back to the General Issues Committee on the progress toward that end in six months;

(e) That any long-term lease or operating and management agreement and use provide for reasonable public access to the buildings and grounds;

( f ) That any proposed use aligns with the provisions in the Heritage Conservation Easement and that the Ontario Heritage Trust be consulted on this alignment for agreement; and,

(g) That, in the event no lessee or management and operations interest, can be secured after a period of one year, Planning & Economic Development Department staff be directed to report to the General Issues Committee with a work plan for the adaptive reuse of the Auchmar Estate.

The Friends of Auchmar reaction:

“We are thrilled with the city council’s decision today to Keep Auchmar in Public Hands. Ultimately, this is the right way to go. We are confident that ultimately a sustainable adaptive reuse plan will come together for the Auchmar Estate.” (www.friendsofauchmar.ca/news)

Comments 0

There are no comments

Add comment